Press release

"Around 1926 Kirchner's talent had brought about a new achievement, insofar as it unified everything he had accomplished earlier in a new technique that approached the frugality of his earlier works, yielding visionary compositions.”

With these words, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, under the pseudonym of Louis de Masalle, an art critic, stressed the importance of his late work. Art historians have often discussed the significance of these works within Kirchner’s oeuvre, as well as the precise characteristics and timing of his “late work”. What have been mostly undervalued in these discussions are the innovative aspects of the paintings, which, seven decades after Kirchner’s suicide, still appear fresh and at times strikingly close to contemporary painting. For this reason, and to deepen the discussion about the importance of Kirchner's late work, it is worth a fresh look at the works made in Switzerland by this important and influential German artist. Thus, Julius Werner Berlin proudly presents rarely exhibited important paintings and numerous drawings by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, made in Davos, Switzerland, in the 1920s and 30s.

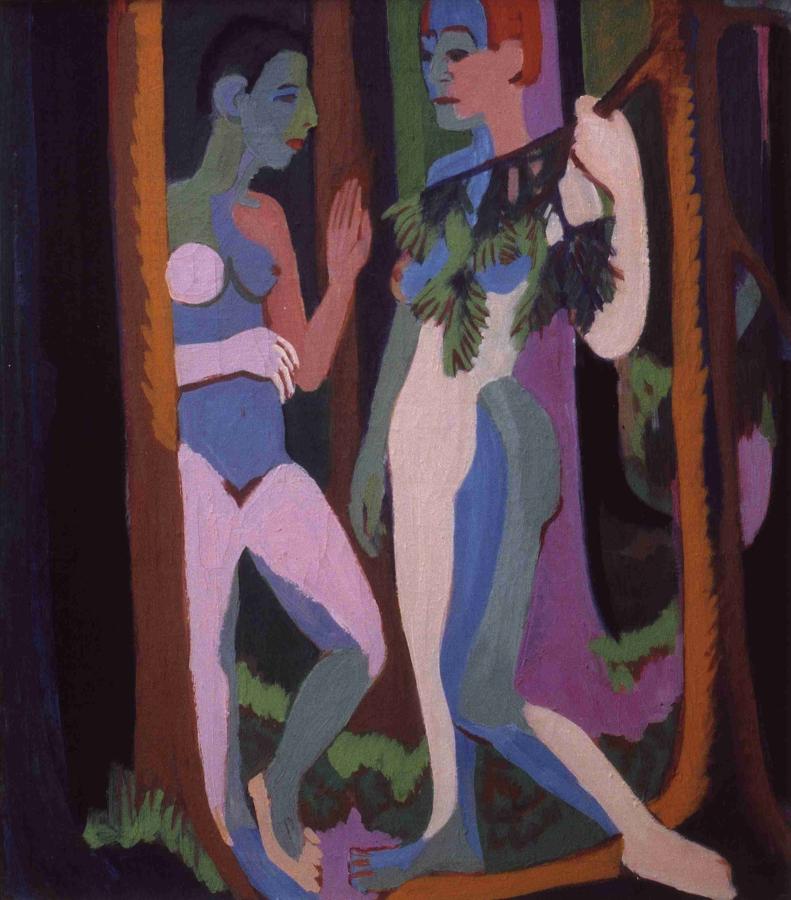

Together with Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, Erich Heckel and Fritz Bleyl, Kirchner was one of the founding members of the artists' association “Die Brücke” (the "bridge"). Founded in 1905 in Dresden, “Die Brücke” paved the way for Expressionism in the German-speaking countries. In 1917 Kirchner moved to Davos, with the hope that he could recover from his poor health and in particular a war-induced nervous breakdown. It was there in Davos, around 1924, that a new style emerged. Different from his Berlin style, which was characterized by motifs taken from urban life painted in rapid zigzag brush strokes, the “Davos paintings” were mostly taken from his fantasies inspired by the intense beauty of the new natural environment, given a geometric-abstract treatment and depicted with near hallucinatory color combinations. In these paintings Kirchner no longer tried to capture vibrant urban life, but strove instead toward abstraction, influenced by contemporary avant-garde painting. Yet Kirchner’s interest

in the formal aspects of painting was not new; it was rooted in his early Dresden years, also a time in which he searched for a "new style", and his interest in the applied art of the tapestry. In Davos, he returned to textile art to find strong formal solutions for organizing form and color. Thus, the formal questions Kirchner explored in his Davos years were old ones, yet the answers he found were progressive.

The exhibition is accompanied by a full-color catalogue (102 pages, 82 mostly full page illustrations) with an essay by Dr. Pamela Kort in German and English.